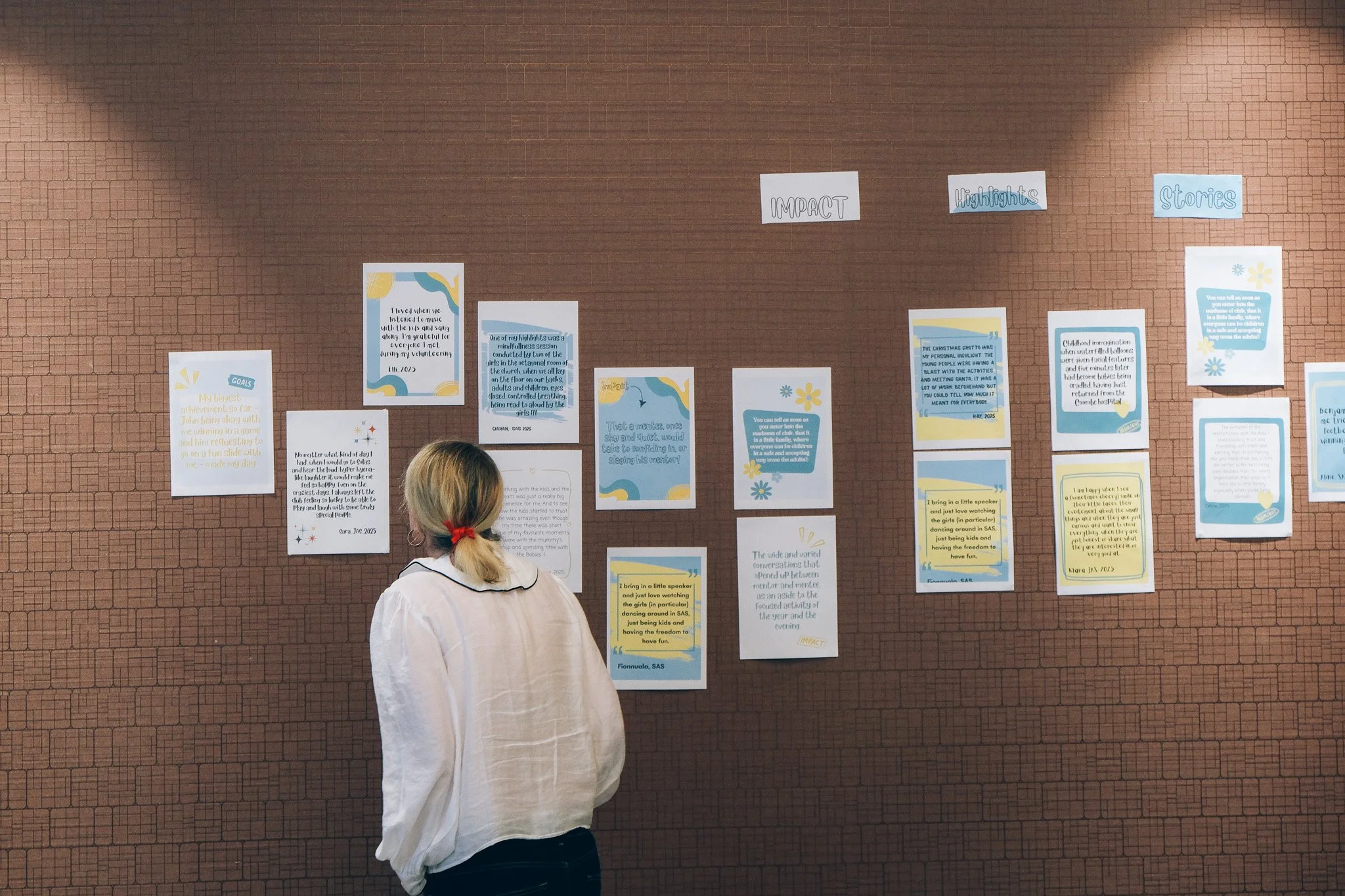

Youth Justice in Action: Court Accompaniment Training Across Ireland

/Dowling and Golden with Niall Collins (Minister of State at the Department of Justice)

When people think of Youth Justice work, they often picture community outreach or mentoring. But a less visible, equally important part of our work is supporting children and young people through the court process. For many, walking into a courtroom can feel overwhelming and isolating, which is why our Youth Justice Workers stand alongside them to offer guidance and support.

In collaboration with Victim Support at Court (V-SAC) and with input from the Probation Service, our Youth Justice team members, Ashling Golden and Shauna Dowling, have been delivering Court Accompaniment training for Youth Justice Workers across Ireland. Funded by the Department of Justice, Home Affairs and Migration, this training is being rolled out nationwide with the goal of equipping more than 500 Youth Justice Workers by the end of 2025.

The training introduces a new system where Youth Justice Workers accompany young people before the courts, offering informal support and clear explanations of court procedures. At the most recent training session in Limerick, Minister of State Niall Collins attended and shared:

“Legal terminology and language, court processes and procedures, the flow of legal argument and what can and cannot be said in Court can be difficult or even impossible for a layperson to navigate and understand. Many young people who are engaged with YDPs (Youth Diversion Projects) may come from a background of educational disengagement or disadvantage, which can negatively impact on their ability to understand the Court process.

This Scheme aims to assist these young people and ensure fairness in the justice system.”

As expressed by minister Collins, many young people in our justice system are educationally disengaged or disadvantaged, therefore by helping Youth Justice Workers provide this kind of support, the training plays a vital role in ensuring that young people are not left to navigate the court system alone.

Court Accompaniment training in the Absolute Hotel, Limerick, August 2025.

youth workers from Crosscare who completed the Court Accompaniment Training.

According to Youth Justice Workers who have completed the training:

“I was glued to the training from the very start, loads to learn and loads to consider.”

- Cork Participant“I thought I would just learn about the court systems which I did but also how to deal with challenging situations I hadn't really considered beforehand.”

- Dublin Participant

This work aligns with our fourth Strategic Goal: advocacy to affect change, by ensuring young people’s voices are heard directly and continuing to work towards a shift in societal attitudes on how young people are treated in court; placing their rights and humanity at the heart of Youth Justice in Ireland.